q2w

Bold Street is my favourite place in Liverpool; a quirky, alternative spot, home to some fabulous places to eat, international and organic food retailers and ethnic and arts shops. Look towards the top of Bold Street with your back to the city centre and you will see what first appears to be an ordinary church; but things are not always what they seem. Any native of Liverpool will be able to tell you why this church, St. Luke’s, is different. For those who are not ‘in the know’, keep on walking and you’ll find out…….

St Luke’s, colloquially known as the ‘bombed out church’, stands as a proud shell of its former self – literally. It was built to serve the Anglican community of city centre Liverpool after Lord Derby granted the land on Leece Street to the Church of England in 1791, apparently on condition that it be always used as a church and that no burials take place there. The building was completed in 1831.

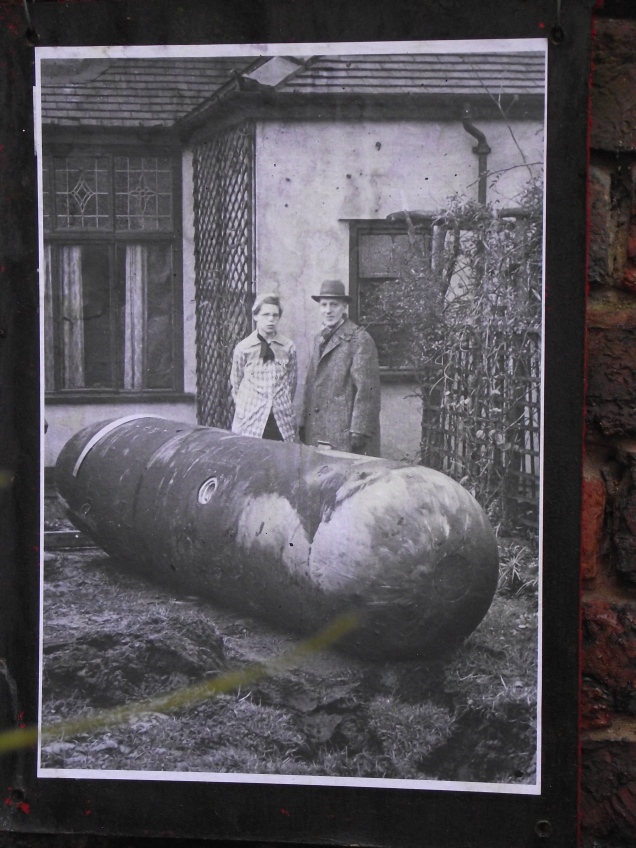

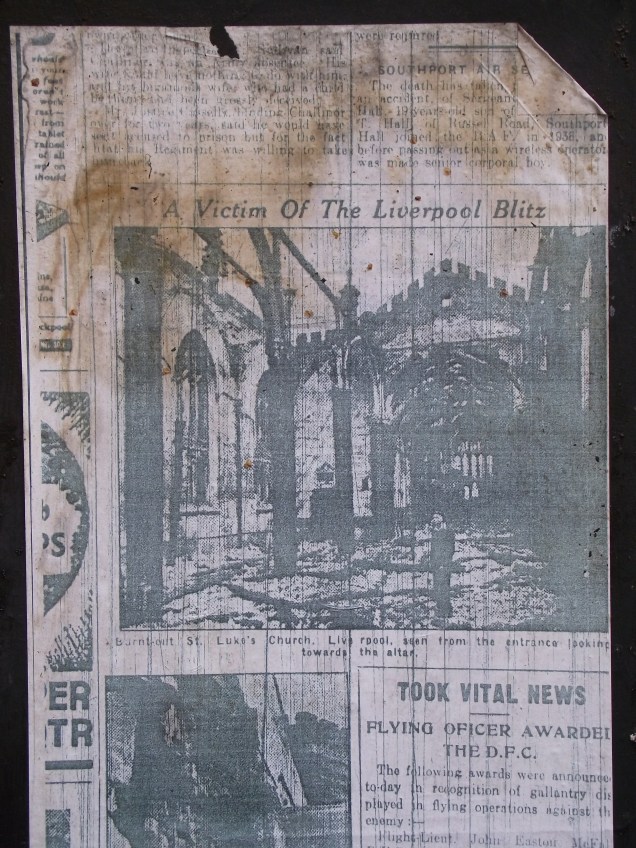

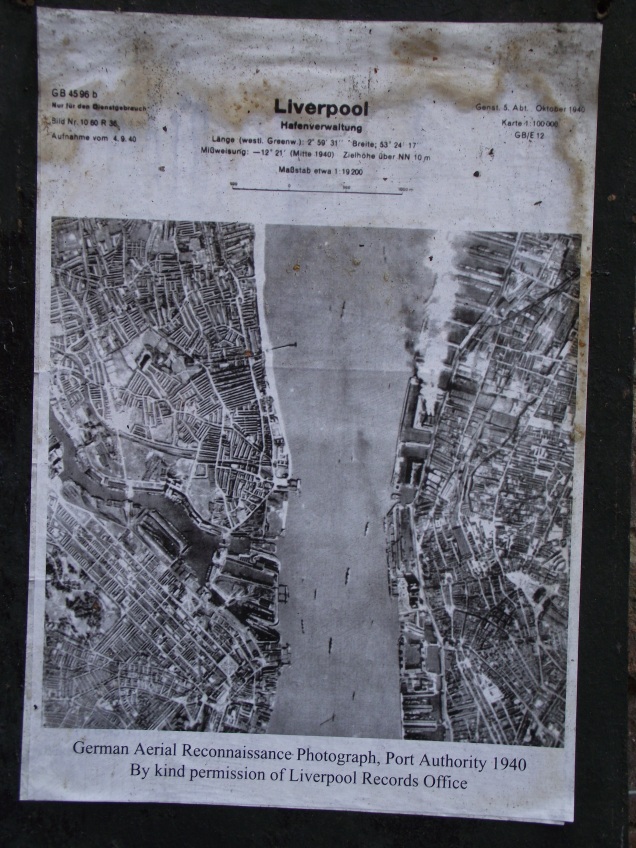

The good people of the city worshipped uninterrupted at St. Luke’s for over a hundred years until a fateful day in the spring of 1941. Britain was at war with Germany and nightly air raids were commonplace, affecting many British towns and cities. Outside of London, Liverpool was the most targeted location in the country, due to it being a major port. In May of that year, the German Luftwaffe attacked Liverpool for seven days in a row. St Luke’s was hit by an incendiary device, thankfully at a time when nobody was within. The church blazed for three days before finally revealing all that was left – a roofless shell. Some photographs of the blitzed city and church are displayed within the modern space.

After the war, Liverpool Council planned to demolish the remains of the church, but there was a public outcry; to the people of the city, the ‘bombed out church’ was a symbol of survival and strength. Happily, the plans were dropped, but over the years the site became neglected.

About fourteen years ago Ambrose Reynolds, founder of local arts organisation Strawberry Urban Lunch, sparked a regeneration of interest in St. Luke’s by using it to host arts events in commemoration of the blitz and its survivors. Within a few years he was granted stewardship of St. Luke’s and through a lot of hard work and receipt of financial support, he and his team were able to open the space to the public once again.

The building has been put to some creative uses during the last decade, including live music and outdoor cinema events, educational projects and art exhibitions. It has even been a wedding venue. Paul McCartney and Yoko Ono have counted amongst its patrons, though despite the high-profile support, St Luke’s has struggled for its survival over the last few years as austerity cuts have hit the north west particularly hard. Ambrose Reynolds and his team have fought this all the way, determined to preserve this amazing space and living museum for the city of Liverpool. Thanks to sheer hard work and determination and whatever financial support they have been able to get their hands on, these brilliant people have been able to secure the future of the bombed-out church, at least for the next thirty years.

The space is currently used for an eclectic range of activities from daily Tai chi and yoga through to performance art. The thing I really love about this special little place in the big city is that it has not, despite its iconic status, developed affected arty airs; it stands in simplicity, displaying its war wounds: charred timbers, glassless windows and warped metalwork, a real symbol that life goes on and human spirit survives conflict.